Pizza Hut is deploying robotic waiters in its restaurants in Asia. Johnson & Johnson is using AI to help parents customize their child’s sleepcare. Unilever is trying to use blockchain to improve its ad buying. The list of non-tech companies experimenting with ‘buzzwordy’ tech goes on and on.

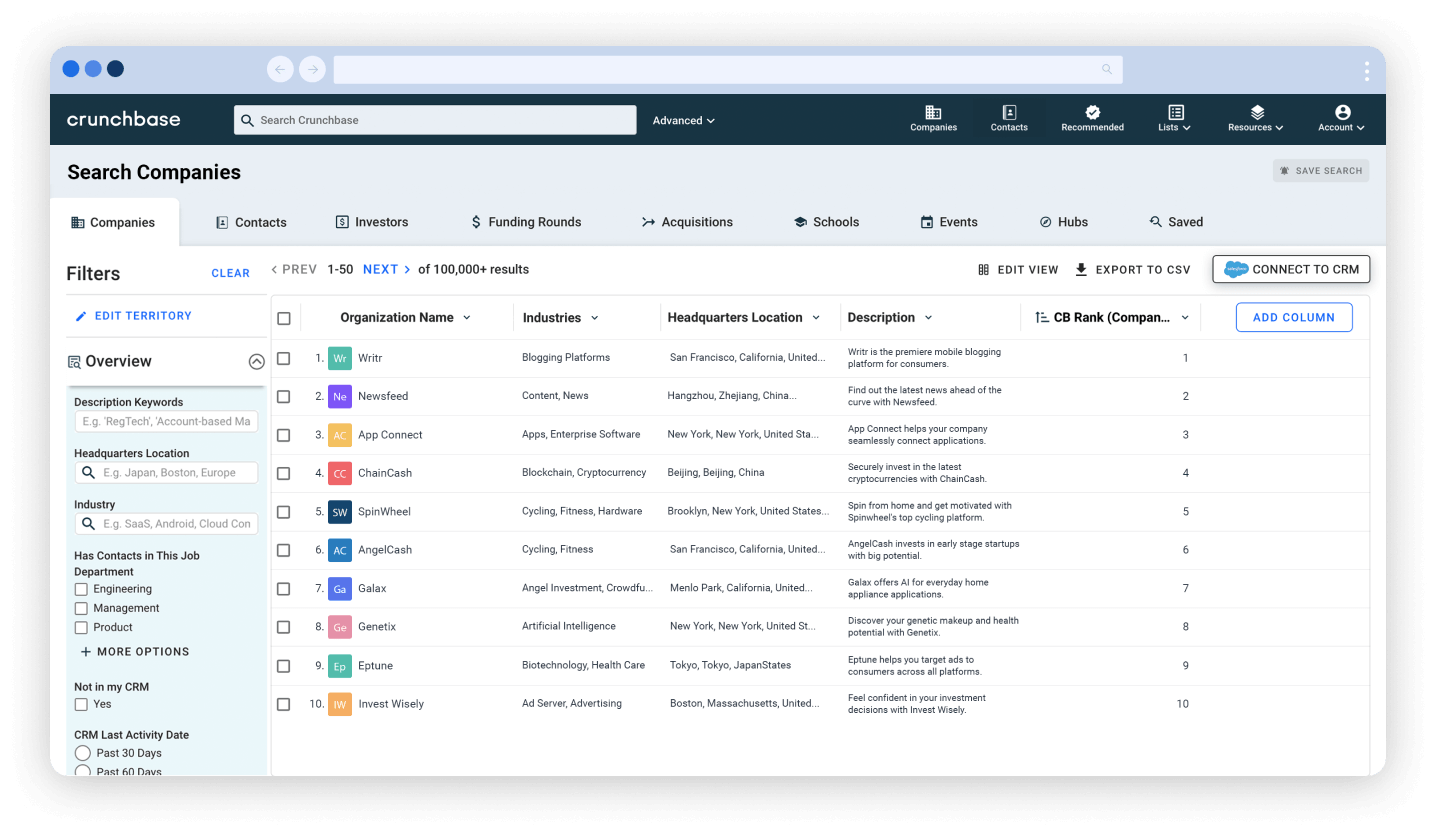

Monitor your competition and upgrade to Crunchbase Pro.

But here’s the thing: adopting––and then successfully implementing––innovative technologies requires more than just investing in robots, AI, and blockchain. It requires a fundamental understanding of the concepts and processes that have enabled tech companies to thrive and dominate the corporate landscape of today. For most old-school companies and non-tech companies, this often means reworking many of their core processes and fundamental beliefs.

Tech buzzwords explained:

AI—regression

Big data—data

Blockchain—database

Algorithm—automated decision-making

Cloud—Internet

Crypto—cryptocurrency

Dark web—Onion service

Data science—statistics done by nonstatisticians

Disruption—competition

Viral—popular

IoT—malware-ready device— Arvind Narayanan (@random_walker) March 22, 2018

Here are a few tech-pioneered concepts and processes which could prove particularly transformative for more traditional, non-tech companies.

How non-tech companies can thrive in a digital world

1: Transparent pricing

In many traditional industries—whether it’s restaurant supplies, TV advertising, or supplement manufacturing—it can take potential customers weeks to get a simple price quote for their order. First, you have to speak to multiple different reps (often telling them the same information). Then navigate opaque monopolistic supply chains. Finally, you’ll get multiple quotes to understand if you are being scammed or not, among other painful, mind-numbingly tedious tasks. To say the process is inefficient would be an understatement.

Compare that with how easy it is to buy an ad on Google or Facebook, in which pricing options are transparent and accessible. It’s night and day.

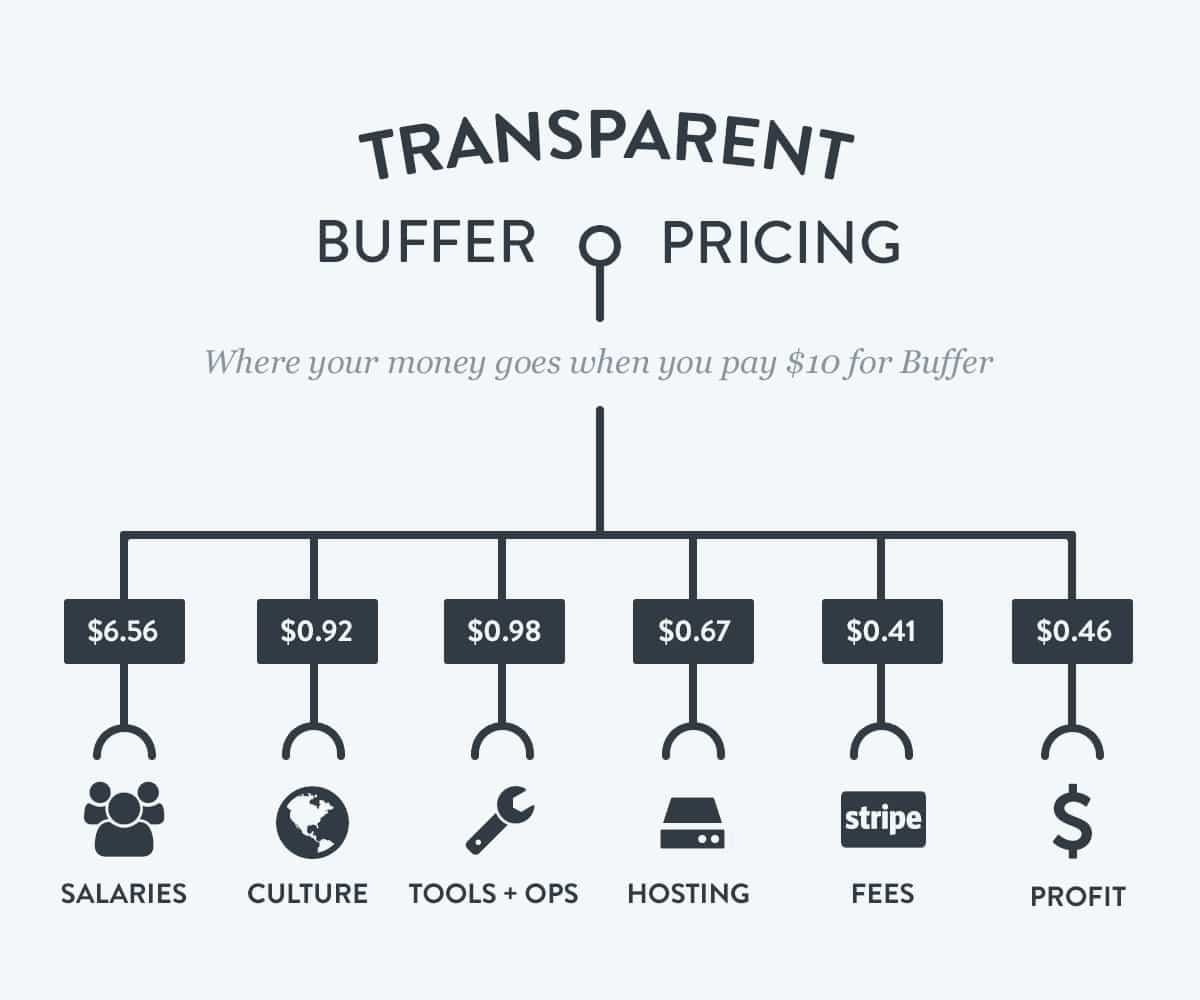

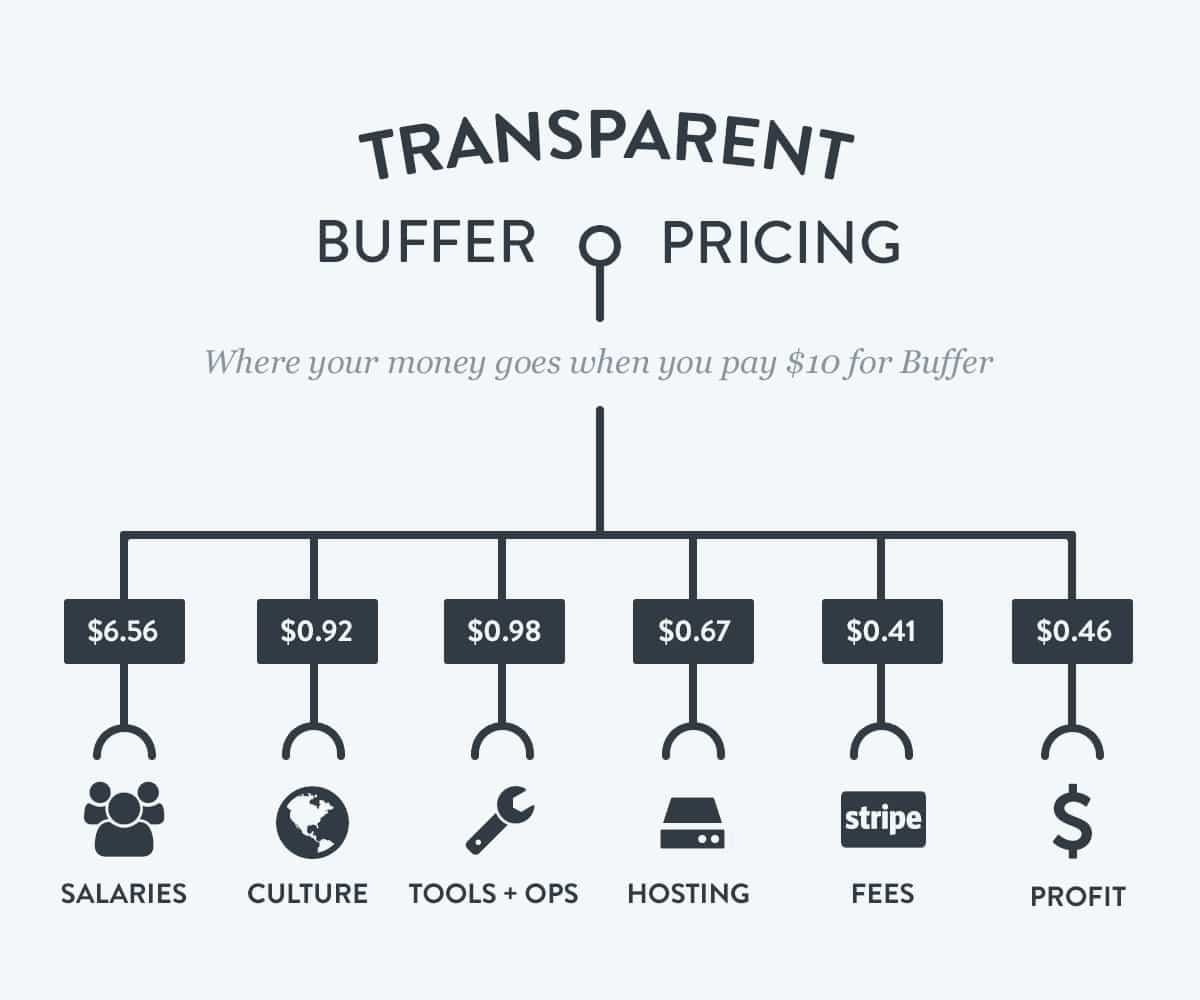

Non-tech companies can use social media company, Buffer’s model when thinking about transparent pricing. Source: Buffer blog

But the thing is, now that we as consumers know that a seamless process is possible, our expectations have changed. This type of seamless process is not just “nice-to-have” at this point. It has now become, “If you don’t have it, I’ll find somebody else who does.” Consumers want simple processes where they can get their answers easily and quickly.

Companies who meet that demand will have a clear-cut advantage; and those that don’t… well, I don’t see them being around much longer unless the government forces you to use them or subsidizes them completely (yes, I’m talking about you, U.S. Postal Service).

2: Dynamic pricing

This is something we all learned back in Econ 101. If the demand for your product or service is high and customers are willing to pay more for it, it doesn’t make sense for you to keep your prices static.

It’s a matter of uncapping your customers’ max spend potential.

Uber’s surge pricing is a great example. Surge pricing has allowed Uber to redefine the scarcity economics of the personal transportation market.

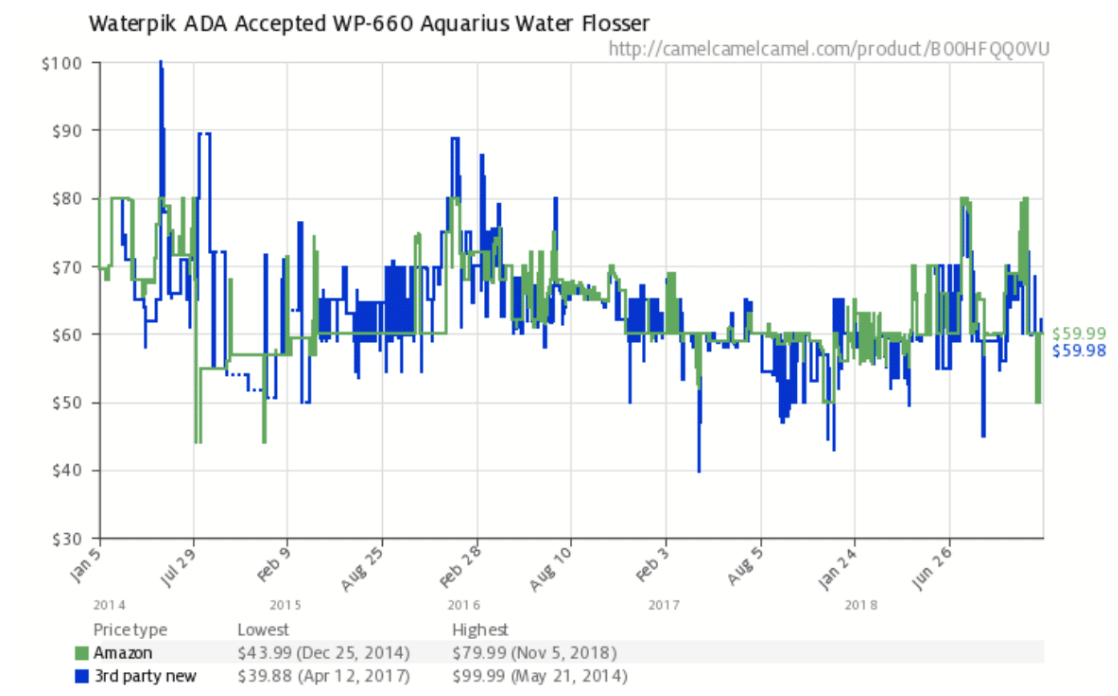

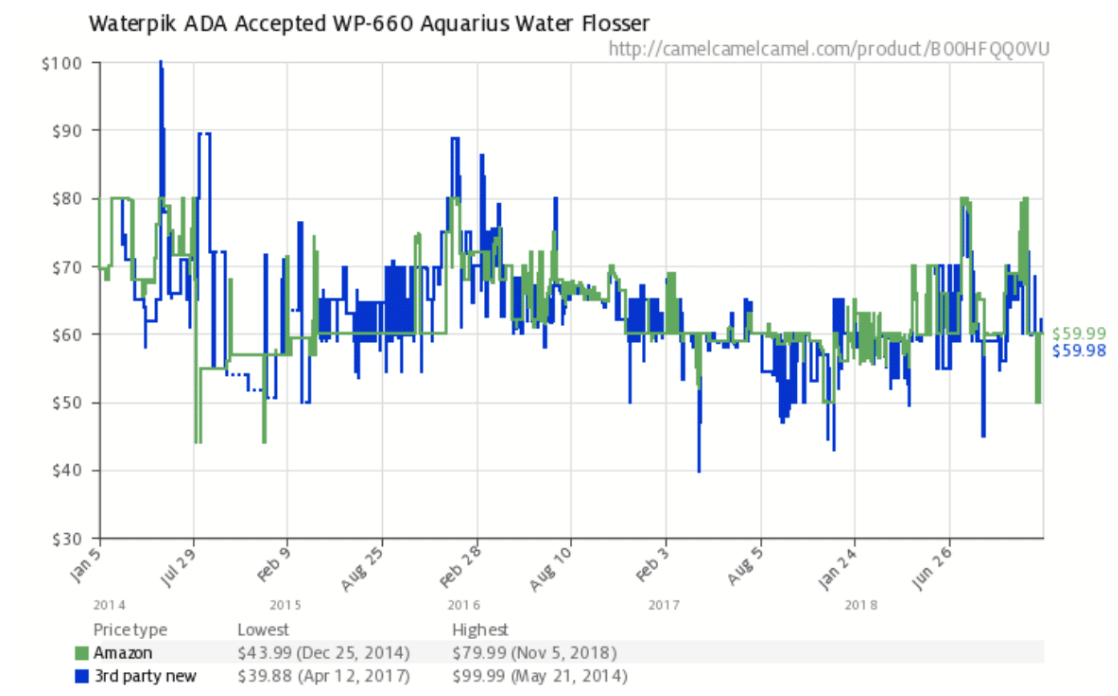

E-Commerce is another space that has leveraged dynamic pricing very well. Above is a 3-year price chart of a Waterpik Water Flosser on Amazon. As you can see, the prices have fluctuated constantly. Prices have varied as much as 250% between the minimum and maximum amounts.

Some traditional players do use dynamic pricing, too, like airlines, hotels, and the MLB, but many don’t, offering only one flat rate. In the end, having a static pricing model is just leaving money on the table.

3: Pay-per-use business models

A great pioneer of this has been Amazon Web Services, the most successful cloud infrastructure service on the planet. As of last year, this single Amazon department had made roughly $10 billion in profit. There’s a lot that accounts for AWS’s success––and removing customers’ CapEx concerns entirely is one major factor.

There are some companies trying this now in more traditional industries, too. For example, Travis Kalanick’s new CloudKitchens is trying to do this with restaurant real estate. Metromile is doing this with car insurance (charging customers for car insurance by the mile). ZipCar, Getaround, and Turo have been doing this successfully with urban car usage, too.

What these companies show is that no What these companies show is that no matter your industry, with enough thought (and tech under the hood), it is possible to ditch the middleman and revamp your bulk pricing structures for something more efficient.

4: Testing product features and demand before doing development

Tuft & Needle––a company now doing more than $100M in yearly revenue––didn’t just create a great product and start selling it on a whim. Rather, they only launched after running different product concepts to different landing pages and testing, purposefully, which concepts resulted in conversions. There is a great podcast with Tuft & Needle’s co-founder JT Marino that talks about this part of their pre-launch journey.

Testing a bunch of ‘fake products’––which look legitimate but are not actually ready for sale––is a common practice for e-commerce startups. Justin Mares talks about how he validated the idea for his new bone broth startup, Kettle & Fire, in about two weeks and for under $100 in a great Sumo blog post.

It’s easy to run Facebook ads to a lot of different concepts and see what resonates and with whom. $500 of Facebook ads and 30 minutes of setup could literally save your company millions of dollars. However, even with all this easy pre-development testing available, many companies today still commit major R&D dollars into a product before they’re confident it will sell.

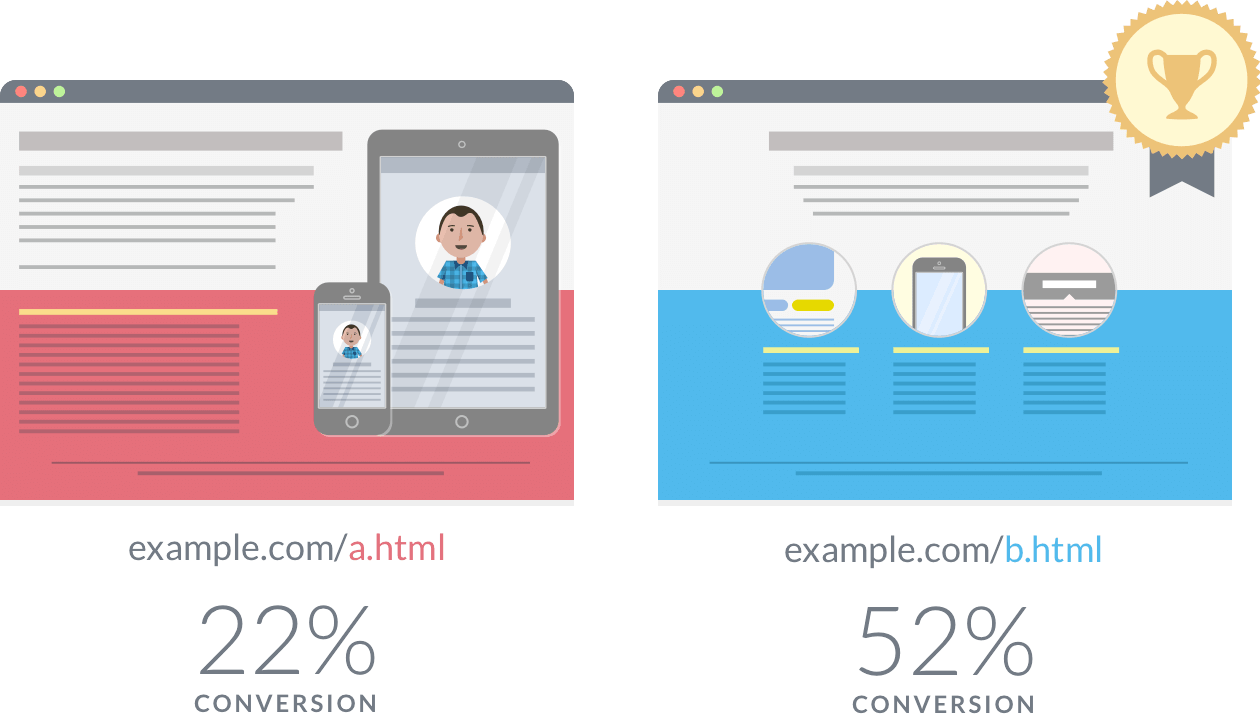

5: A/B testing branding

Similarly to testing product features and demand, many tech companies also test a lot of branding and design changes at a small scale before committing to them at large. We did this a lot at Glu Mobile and Dairy Free Games when working on new game concepts.

The timeline for developing a AAA game is often multiple years. Developers will frequently test many variations of their theme, art style, icons, branding, etc. These tests are just mockup graphics and simulated videos. Gaming studios will then run those assets through specialized testing tools, like Splitmetrics and StoreMaven, that take the ad clicker to a simulated app store.

But even outside of just gaming, this is a common practice in the tech industry to test everything before sending it out to customers. Email subject lines are the most obvious example.

A more extreme example is Marissa Meyer testing 41 different shades of blue in the design process at Google. If you’re just starting out with this, the Optimizely blog has a lot of ideas on design and branding elements that you can A/B test.

6: Personalization

If you can promise customers a more personalized or customizable experience, they’ll either pay more for your product, convert faster, or use your product longer. Over the long run, all of this leads to more revenue.

A good example of personalization, again, comes from mobile gaming. Just look at the top-performing games like Clash Royale, Game of War, or Contest of Champions. Many of the deals that they offer in their stores are highly personalized. The deals are aimed to solve an immediate need for the specific player who sees the offer.

There are also countless mainstream examples of successful personalization spearheaded by consumer tech companies. Amazon, Netflix, Pandora, and Spotify have all built sophisticated personalization and recommendation algorithms to give each user just the right product, show, or song at just the right time.

Personalization is often overlooked in marketing and SEO by non-tech companies. Similarly, Zapier personalized thousands of landing pages to be hyper-targeted to their users’ search queries.

As their CEO, Wade Foster, explains: “We set up landing pages for every combination of app-to-app that you could possibly connect. So if you’re searching for Groove and JIRA, ideally Zapier is in the results.”

7: Deep analytics on everything to quantify what’s working and what isn’t

In order to do any of the this, however––to A/B test, personalize products, or offer dynamic pricing––your company must run sound analytics.

You have to understand what affects your users’ behavior. You must discern why certain products sell well, or why certain campaigns perform well, and others don’t. And in order to do this effectively, you need to invest in your analytics infrastructure. Unfortunately, most companies—even tech companies—overlook their analytics tooling because it doesn’t qualify as something that is “core product.”

Zynga disproves that. They were, in fact, one of the companies that spearheaded effective big data analytics. Some have even said that Zynga is really a “Big Data Company Disguised as a Gaming Company.” Mark Pincus, Zynga’s founder, bet big on data. As he explains on the Masters of Scale podcast:

“We were pushing it more than anybody because we went to tracking every click and analyzing it at a time that they were using Google Analytics. And we were investing so much and we had so many people on it that we kept getting called stupid, that people said, ‘Zynga has 50 people and this company is doing the same thing with 10. Zynga has 300 people and this company is doing the same with 20 or 50…’ because we wanted to over-invest in knowing the data.”

8: Gamification

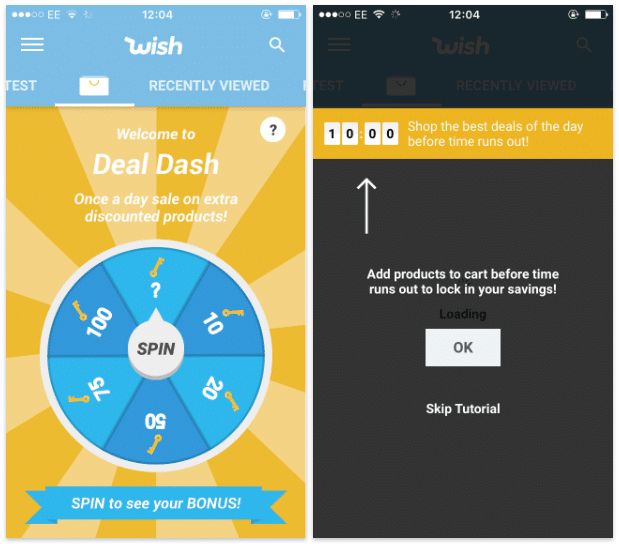

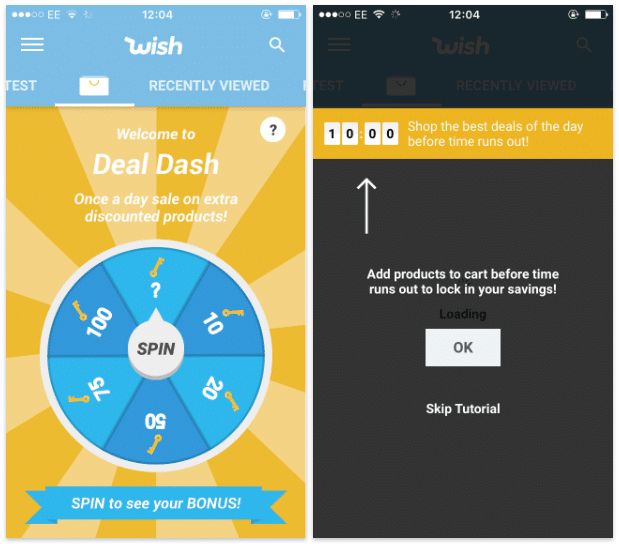

If you’ve bought anything on Wish.com recently––which is on track to do over $2 billion in revenue this year––you’ve probably seen many gamified elements in their store. You can spin the wheel for a once-a-day Deal Dash discount. You can earn reward points with each purchase. And almost everything, from an Instant Offer to your checkout process, has some countdown timer attached to it.

While Wish has perhaps taken gamification elements to an extreme, many marketplaces and review platforms, like eBay, Yelp, and Airbnb, offer gamified elements to their users, too. These platforms use gamification to incentivize the types of user behaviors they want to see on their platforms.

9: Developing compulsion loops

Up until recently, compulsion loops have been a sort of hidden concept, one that tech companies exploited stealthily. This changed when EA became a hot subject of a “loot box” controversy.

One of the most popularized examples of compulsion loops is “loot boxes”. At their core, they’re what psychologists call skinner boxes: things that give users variable rewards for the same repeated action.

Simply rewarding someone every time when they do an action is NOT the best way to have them continue doing that action. Instead, it’s a lot more addicting and motivating to vary up both the reward itself and the likelihood of getting that reward.

This is the reason gambling (and gaming) is more addicting. It’s more stimulating than a predictable, fixed-reward task, like a job that pays a fixed steady wage.

Subscription commerce startups, like Birchbox and LootCrate, are good examples of companies built around the simple compulsion loop of variable rewards. They deliver a novel set of goods to the subscriber each month. A more old-school example of this is Pokemon cards. Pokemon cards effectively were a physical loot box and a highly addicting one at that. If you’re interested in exploring how to apply compulsion loops (and other gaming concepts) to real-world scenarios, I recommend taking a read through Jane McGonigal’s book, Reality is Broken.

Final thoughts

Over time, a lot of the tech-pioneered fundamentals that I’ve covered above will become the new standard. They will span across traditional industries, be it manufacturing, consumer packaged goods, or real estate.

Consumers’ expectations are shifting toward easier, faster, and more personalized experiences. The companies that are able to deliver on those pillars will be the ones that survive.

So, when it comes to adopting new tech, it’s critical that companies think through their processes. Non-tech companies must consider supply chains and strategies at a more fundamental level instead of just building buzzwords on top of a rotting foundation.

Dennis Zdonov is a Head of Studio at Glu Mobile. He runs a studio of about 30 people and concentrates on real-time multiplayer games. Previously, he was the co-founder of Dairy Free Games. Dairy Free Games was acquired by Glu in August 2017. He was also the co-founder of TrackingSocial, a social media analytics company that he and his partner spun into art investing.