Geography has not been very kind to Armenia. Stuck in the Caucasus Mountains between Eastern Europe and West Asia, this country has scarce natural resources and no access to seas. It is not crossed by international trade routes, and many of its borders are closed due to conflicts with some of its neighbors.

Among the most ancient nations in the world, but deprived of statehood for centuries, Armenia also had a tragic recent history — from the 1915 genocide under Ottoman rule to Soviet dictatorship to the economic collapse after the country became independent in 1991.

The recent years were turbulent too, with a democratic revolution in 2018, a pandemic, and repeated conflicts with Azerbaijan in 2020-23 — as well as massive inflows of Russian and Belarusian citizens fleeing their countries at war beginning in February 2022.

Yet, brilliant intellectual traditions, top-notch scientific research, and technological achievements have also come to fruition in Armenia. Aware that their country’s future, and perhaps even survival, mostly depends on its human capital, thousands of Armenian researchers, tech engineers, and entrepreneurs are at work, while a huge diaspora is connecting them to some of the world’s most advanced innovation hubs.

Armenia in numbers

| Surface | 29,743 km2 |

| Permanent population (2022) | 2.93 million (census) |

| Armenian diaspora | 5-10 million |

| GDP (2022) | $19.6 billion (World Bank) |

| GDP per capita (2022) | $7,014 (World Bank) |

| GDP growth (2022 / 2021) | 12.6% (World Bank) |

| Tertiary education rate (2021) | 55.4% (Unesco) |

| Information and Communication Technology (ICT) workforce (late 2022) | 44,000 (EVN Report) |

High growth, tiny ecosystem

Armenia’s tech sector has been skyrocketing over the past 10 years, with an IT workforce growing fourfold to some 44,000 professionals in late 2022 and a CAGR exceeding 20%. At least 18 global corporations have established innovation hubs in Armenia, according to a recent report by Innotechnics, leveraging local talent from programming to chip design. High-technology products account for nearly 6% of the country’s total exports, according to World Bank. And while Armenian outsourcing companies have asserted themselves on the global market, companies have recently emerged that build globally competitive solutions to problems faced by people all over the world.

With some 500 active startups, according to insiders’ best estimates, Armenia’s tech ecosystem still looks embryonic. But it already generates world-class tech companies, in tight connection with the U.S. market and with support from the diaspora. And, many first-generation startups already exited to global tech corporations — from Cisco to Deloitte, Oracle, Playrix, Synopsys or VMWare.

Two U.S.-based unicorns — Picsart and ServiceTitan — were founded in Armenia or by Armenians, placing the country on par with or ahead of its neighbors.

Armenian startups aim to be global from Day One, using the tiny domestic market as a testbench to fine-tune their products. They tend to move abroad — mainly to the U.S. — as soon as they start gaining traction. However, many of them maintain R&D activity in their country of origin.

“Armenian startup entrepreneurs have a global mindset. They immediately think of California because of the connections they can leverage there to find working spaces, investors, customers, research partners from universities,” said Ashot Arzumanyan, partner at SmartGateVC, a fund bridging the two countries.

Picsart did follow this path. Born in Armenia in 2011, the photo- and video-editing platform began expanding to the U.S. in 2015, following a Series A funding round involving Sequoia Capital. It settled in San Francisco, then Miami, keeping a team in Armenia that continues to be a major piece of the company in a multicultural corporate context. Picsart became a unicorn in 2021 when it raised $130 million in its latest round involving top international investors.

Armenian IT outsourcing and software development companies are less U.S.-centric than its startups. Instigate Robotics, a developer of industrial automation systems, UAVs, and advanced education systems, started sales in the U.S., but diversified toward the EU and Asia, which now account for half of its revenue. Volo, another major outsourcing company, generates 54% of its revenue in the U.S./Canada, 40% in the EU and a bit in the U.K.

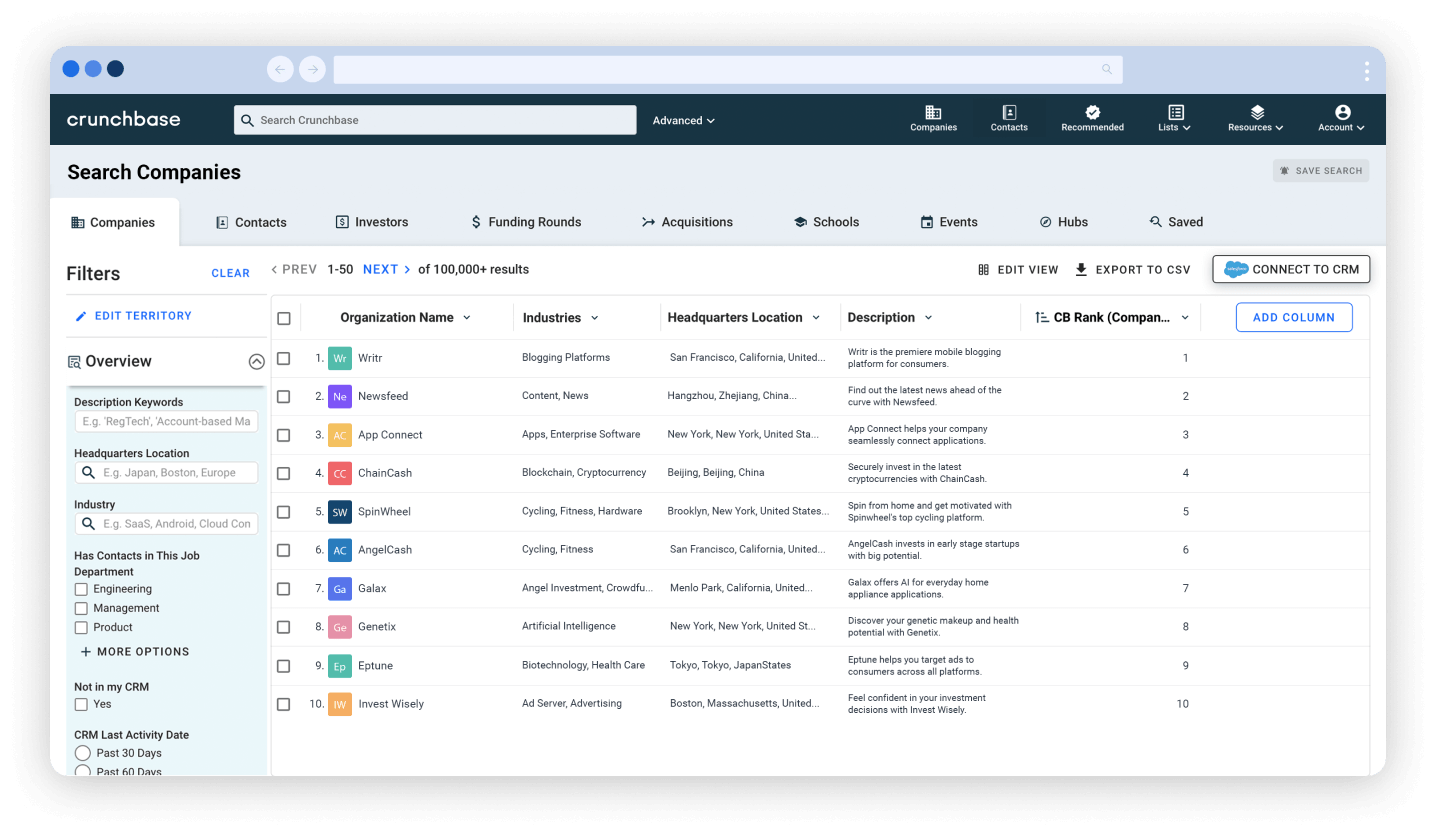

Examples of Armenia-born or Armenian-founded international startups with funding exceeding $10 million

| Startup | Segment | Headquarters | Total funding amount* |

| CodeSignal | Interview and assessment solution for technical recruitment | California | $87.5M |

| Disqo | Audience insights platform to connect brands and people | California | $101.5M |

| IntelinAir | Aerial imagery analytics for agribusiness | California | $24.9M |

| Krisp | AI-powered voice clarity and meeting solution | California | $17.5M |

| Picsart | Photo and video editing + community | Florida | $195M |

| Renderforest | Online design tools | Armenia | $20.1M |

| ServiceTitan | Management software for home services businesses | California | $1.1B |

| SoloLearn | Code learning platform | California | $30.9M |

| SuperAnnotate | Enterprise solution to build and manage AI models | California | $17.5M |

| Zero Systems | AI knowledge management solution | California | $12.1M |

The local venture market is taking shape, with a half-dozen active funds and three main business angel networks. Given the small number of investable startups on Armenian soil, these few investors generally cover funding needs at the pre-seed and seed stages.

“Strong, globally oriented entrepreneurs are likely to raise funds locally,” said Grigor Hovhannisyan, who heads the Business Angel Network of Armenia.

“A few years ago, you couldn’t imagine raising $400,000 locally. But in late 2021, BANA provided $500,000 to a startup at the seed stage, while in early 2023, Prelaunch.com got $1.5 million from local VCs and angels,” he said.

Successful tech entrepreneurs or executives reinject money in fresh startups. For example, the fund BigStory VC was launched in late 2021 by the founders of three top Armenian startups — Krisp, Picsart and Podcastle — with plans to invest $10 million within two years.

Most active venture funds in Armenia

| Fund | Focus |

| BigStory VC | Armenian founders |

| Formula VC | SaaS, IoT and AI from Armenia and nearby regions |

| Granatus Ventures | Impact investing in Armenia and beyond (2nd fund) |

| Hive Ventures | U.S.- and globally-oriented Armenian founders |

| SmartGateVC | AI companies targeting the U.S. market |

| 3S Ventures | Armenian startups |

While practically absent from Armenia itself, international investors step in to back mature Armenia-born or Armenian-founded startups as they gain global traction. SmartGate’s Arzumanyan cites a few notable examples of such funds, including Andrew Ng‘s AI fund, Base10, Bessemer Venture Partners, Felicis Ventures, Learn Capital, Sequoia, Sierra Ventures and True Ventures in the U.S., as well as Dutch Acrobator Ventures, Germany’s Point9 and 468 Capital, and DCM.

Some international investors are involved in Armenia-focused funds. Thus Tim Draper and One Way Ventures are limited partners in SmartGateVC, while institutional investors backed the Granatus funds (World Bank and UNDP in 2013 and 2021, respectively).

International institutions also brought significant contributions to building the Armenian ecosystem. Since its launch in 2002, the World Bank has supported the EIF, or Enterprise Incubator Foundation, which is a central piece of Armenia’s innovation ecosystem. Outside the capital, the construction or redesign of two technology centers — in Gyumri and Vanadzor — was made possible by international public funding. The EU, GIZ, World Bank and others have backed a variety of capacity-building grant programs for startups.

Although crucial to support entrepreneurs at the ideation stage, these programs do not always provide a stable framework for startup innovation, since their backers may renew or stop them unpredictably.

The local government is also doing its part. Since 2015, startups and small IT companies have enjoyed tax exemptions, while people employed in the IT industry benefit from a lower income tax rate. Government support got stronger after the 2018 change in power and the creation of a dedicated Ministry of High-Tech Industry. New grant programs (example) were launched, while the recruitment of foreign technical staff has been incentivized, among other measures.

While business registration procedures are generally straightforward and few restrictions are imposed on foreign investment, local legislation still needs improvements when it comes to risk investment.

In 2020-2022, FAST, or the Foundation for Armenian Science and Technology, and its affiliate Science, and Technology Angels Network, collaborated with authorities and EBRD-backed Investment Council of Armenia to establish a SAFE agreement compatible with local legislation. “We’re expecting soon new legislation for risk investment. Paired with reforms in arbitration, this can change in the long run the legal environment on the ground,” notes Suzanna Shamakhyan, VP of strategic programming at FAST.

Diaspora-enabled innovation

To a significant extent, Armenia’s bid for technology development relies on its diaspora as a source of expertise, connections and investment — and perhaps one of Armenia’s best competitive advantages.

An estimated 5 to 10 million persons of Armenian descent — several times as much as the domestic population — live outside of the country. Russia, France and the U.S. host the largest communities.

Recent Armenian immigration to the U.S. is concentrated in Los Angeles: From 1987 to 1989, 90% of Armenians leaving the Soviet Union settled there, and they continued arriving massively in the 1990s. “U.S. Armenians are thriving in the field of technology — in Californian startups, in big corps around Seattle, and in Boston working in biotech,” notes Arzumanyan.

A range of diaspora figures are involved in Armenia’s technology developments. Here are some examples:

- Ruben Abagyan is a prominent researcher in the fields of biochemistry and computational chemistry. This year he started a FAST-funded research project on new drug target discovery and chemical modulators.

- Noubar Afeyan, an American-Canadian inventor and billionaire, co-founded Moderna. He is also among the backers of FAST’s angel network.

- Armen Aghajanyan, principal scientist of AI research at Meta, is guiding the development of an AI institute in Armenia.

- Zaven and Sonia Akian have just donated $9 million to launch a bioscience laboratory at the American University of Armenia.

- Naira Hovakimyan, a professor of mechanical science and engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, mentors Yerevan’s National Polytechnic University. She also co-founded IntelinAir as chief scientist.

- University of Maryland chemistry professor Garegin Papoian founded Biosim, a Yerevan-based startup that enables and accelerates drug discovery through AI, quantum mechanics and molecular dynamics.

- Donations from Sam and Sylva Simonian, who are prominent figures of the Armenian diaspora in the U.S., made the creation of a computer science program possible at the American University of Armenia. They have also funded TUMO, a free education program for teenagers with a focus on technology and design.

There are also repatriates who create startups in Armenia. Davit Baghdasaryan, a former senior engineer at Twilio, co-founded Krisp, while SuperAnnotate co-founder Vahan Petrosyan was previously working on his Ph.D. research in Sweden. In 2018, the government, together with the local incubators and investors, launched Neruzh. This program offers grants of up to 30 million AMD ($76,000 at the current exchange rate) to develop the local startup ecosystem through professional repatriation.

“Armenians are known for their strong sense of community. This cultural trait extends to the tech sector: they actively support one another through mentorship, investment and business partnerships,” notes technology investor and entrepreneur Alexander Smbatyan. “But the diaspora also contributes to cross-fertilizing ecosystems and cultures across the world, stimulating Armenians’ creativity and favoring their successes.”

Another diaspora is boosting Armenian tech: Thousands of Russian and Belarusian programmers, startup entrepreneurs and investors came to Yerevan en masse after February 2022, fleeing the draft and political repression in their countries.

According to the Armenian government, around 50,000 Russian IT specialists had arrived in Armenia as of September 2022, at the height of the migration. A portion of them came only temporarily before trying their luck in the Middle East, Asia, Europe or the U.S. But another part — perhaps around 20,000 — stayed in Armenia.

These highly educated IT professionals have helped the country address the shortage of qualified workforce, which strongly hampered technology development.

“Yerevan turned into another sort of tech hub,” wrote data journalist Ani Avetisyan. “Armenia witnessed a nearly 50% surge in the number of registered IT workers in the first four months of 2022,” compared to the same period of the previous year.

The local ecosystem has not absorbed all the relocated Russians. A part of them continued working for their Russian or ex-Russian employer — Miro, Nvidia, Yandex, Quantori, Sberbank or VK. But the integration of the two tech communities is progressing, as has been the case in Central Asia and other relocation areas.

“Some companies from Russia started employing Armenian developers, and vice versa. Teams are mixing very slowly, but increasingly, to become multinational,” said Volo’s CEO Armen Kocharyan.

“Armenia offers very good opportunities for Russian-speaking founders, who can organize their back-office there,” said Sergey Bogdanov, a VC investor who relocated to Yerevan in March 2022 before moving to Lisbon, Portugal.

While active in Armenia, Yellow Rocks launched a co-working space in Yerevan, and invested in two Armenian AI startups, Pearch.ai (previously B4) and Wirestock.

Armenia’s bet on deep-tech

Not that long ago, Armenia was often referred to as “the Silicon Valley of the Soviet Union.” While accounting for just 1.5% of the USSR population, it designed and produced 30% of Soviet electrotechnical equipment, including computers, Vahagn Pogosyan, co-founder at Instigate Robotics reminds us. The republic spent more than 2% of its GDP on R&D.

More than 100,000 people were involved in these activities until the late 1980s. At the epicenter of the local technology industry was the Yerevan Scientific Research Institute of Mathematical Machines (Mergelyan Institute), which then employed more than 10,000 people.

“All these universities and institutions collapsed in the 1990s in Armenia (like elsewhere in the former Soviet Union). Recovery has been very slow and is far from being complete today. In 2021, 30 years after our independence, only 25% of the previous tech talent pool (25,000 people) was recuperated. Until nowadays, scientific research has been underfunded, crippled by brain drain, literally dying in certain fields, and lacked commercialization routes,” said Pogosyan.

The past few years saw some progress, however. State funding of scientific research grew significantly, albeit not sufficiently, while venture capital supply triggered the emergence of a range of deep-tech startups. The unexpected arrival of Russian techies provided another boost to the new industries.

State funding of science in Armenia (in billion AMD)

Cited by Manya Israyelyan in EVN Report. 1 USD = 394 AMD in October 2023

Could Armenia again become a tech nation? “Education, knowledge, and intellectual pursuits are rooted in Armenian cultural traditions. This context has laid a foundation for the development of a mindset that embraces technology and innovation,” Smbatyan believes.

For the moment, Armenia spends just 0.3% of its GDP on research and development — a far cry from technologically advanced countries. It stands 72nd in the WIPO’s Global Innovation Index (out of 132 countries) — but 17th among the 33 upper-middle-income group of countries.

A privately funded nonprofit, FAST is among those pushing Armenia’s tech agenda through a variety of programs for innovators and entrepreneurs. It promotes a vision of “Armenia as a top 10 global innovator nation and a top 5 data science and artificial intelligence innovator by 2041.”

“Let’s be realistic,” concedes FAST’s founding CEO Armen Orujyan: “Today, Armenia fills none of the key requisites: excellent and competitive education, high-performing research, and a high-tech and deep-tech sector that brings major contributions to GDP and exports. Huge efforts should be made in these fields. But look at what this nation has been able to demonstrate in the recent past. Look at the Armenians around the globe who perform exceptionally when operating within fully functional ecosystems — the U.S., France, Russia, and other places. Look at the experience of such countries as Israel, South Korea, and Singapore, which have become tech nations in spite of their limited size and/or geopolitical exposure. All this gives us the conviction that, if we succeed in building our own ecosystem, the nation will respond and perform at a very high level.”

Artificial intelligence is often cited among the segments in which Armenia has the strongest potential.

“There’s a major culture of studying mathematics in the country. Leveraging this, FAST is introducing AI as part of the core curriculum to nearly 400 students in 16 high schools right now — a first in the region and a rare thing in the world. We aim to build ‘Generation AI’,” said Orujyan.

Arzumanyan also sees artificial intelligence as one of the “relatively non-capital-intensive areas where Armenia can build on existing foundations for success.” He highlights the “breakthrough applications” brought by Picsart, Krisp, and SuperAnnotate in such areas as computer vision, noise suppression, and natural language processing.

Armenia should not compete with major AI hubs, but instead “aim to align and integrate activity with existing leaders,” he believes.

The country could also excel in computational biology. Last year saw the creation of the Armenian Bioinformatics Institute in Yerevan, with support from the diaspora. Biosim, founded by University of Maryland professor Garegin Papoian, and Denovo, a creation of FAST’s venture builder Ascent, are two Yerevan-based startups operating in the field of drug discovery.

Armenia’s potential is also cited in such other fields as embedded software, chip design, electronic design automation, robotics, advanced engineering, and new material, as well as the space sector.

For Armenia, science and technology are not only a matter of economic prosperity but also, perhaps, of survival. The country’s geopolitical exposure has been underlined twice in three years in conflicts around Karabakh (Artsakh), and Armenia’s south is believed to be now under threat. From cybersecurity to drones to digital imagery, technology is vital in modern warfare. It is not by chance that the brand-new Ministry of High Tech Industry took over the military industry, aiming to boost, in particular, the production of UAVs.

“There are monumental obstacles on Armenia’s way to a high-tech future. But this is a long-term goal around which the nation can mobilize,“ concludes Orujyan.

The author, Adrien Henni, has more than a decade of venture and startup experience in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. He co-founded International Digital News, a tech news and market research agency covering these regions, and is an adviser to a variety of startups and investors.