I started investing in startups after scaling and selling my second business. After this experience, it became clear to me that there was a need – and an opportunity – to deploy a Silicon Valley-style venture capital firm abroad in Latin America.

I co-founded Magma Partners in 2014 to invest in startups with technology or sales teams in Latin America that were targeting the US market. Over the years, our firm has invested in 50 startups. Over that time I’ve learned a few things about what makes a good startup investment. Our portfolio companies have received over $46M in follow on funding from mostly US funds and bring in $28M+ in yearly sales, even though many were pre-revenue before we invested.

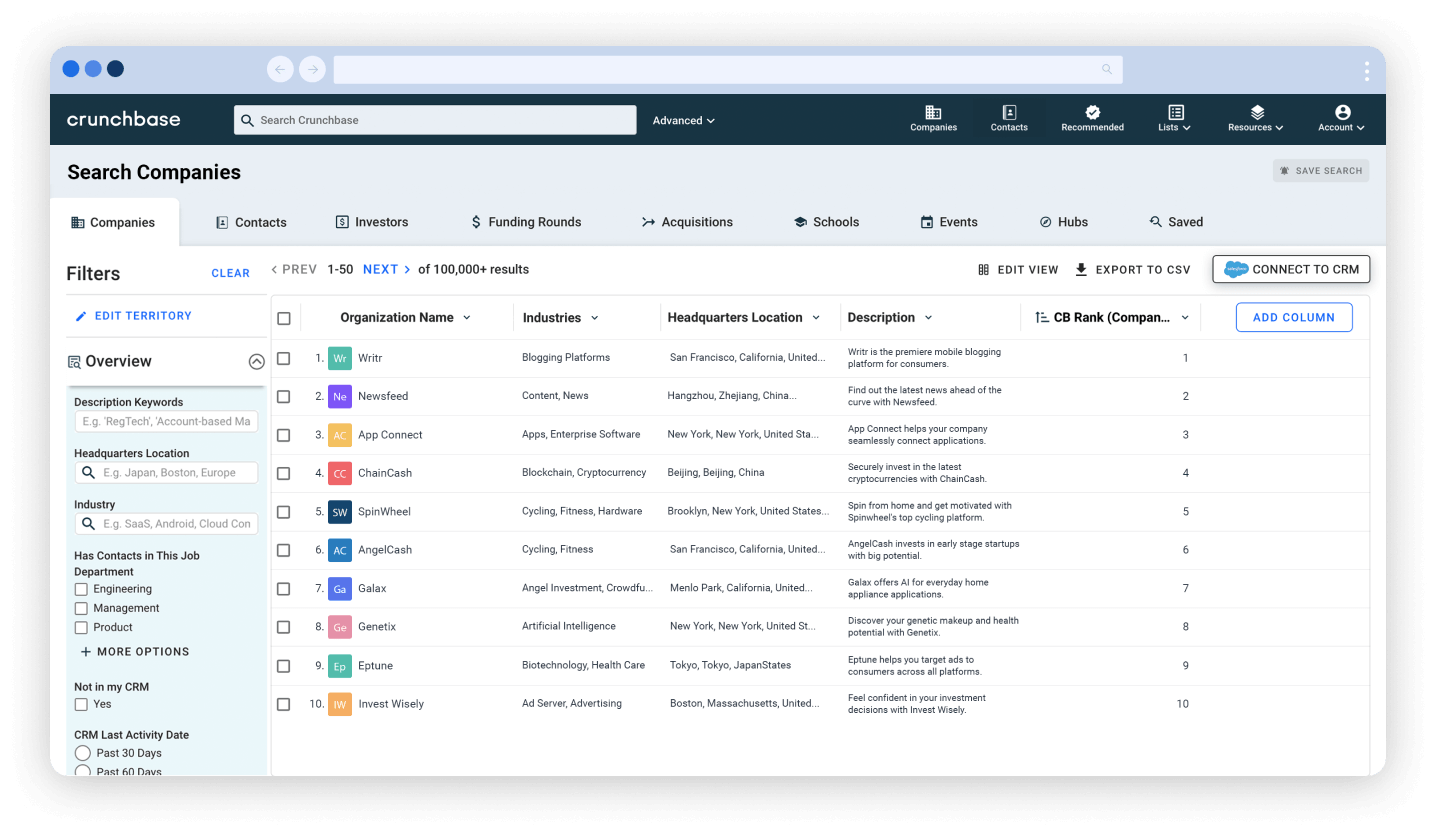

Find your next startup investment or raise capital with Crunchbase Pro – try it free.

In emerging markets, classism is still rampant. While the wealthy are well-connected and might easily be able to work their way into an investor’s office, talented founders from less fortunate backgrounds face significant barriers to “getting the intro” at a VC firm. We believe that talent is evenly spread out, but opportunity is not. Therefore, every startup that applies for investment from us comes through the same online form. Even if we get a formal introduction, we ask founders to spend five minutes giving us some bullets points that we can use to start to evaluate the business. We want our door open 24/7/365.

Questions to ask before you invest in a startup company

No matter how beautifully-designed or well-practiced a pitch, most VCs spend the whole time waiting to hear the nitty-gritty details that affect the investment. For example, the company’s capitalization table, traction, industry knowledge, and the founders’ track record. Our application process asks for this information upfront, allowing us to get straight to the point.

When a startup applies for investment from our firm, here is what I look for first.

1. Is the team well-balanced, dedicated, and focused on the problem?

There are three parts to this question. When we talk about an early-stage startup team, we usually refer to the founders, plus maybe an engineer or salesperson. In most cases, investors prefer to see that these first team members have complementary skill sets and a similar motivation to solve the problem. The team should be able to clarify this information with their answer to the question, “Why did you start this business together?”

Before we invest in a startup, I also like to evaluate what this team looks like in practice. First of all, having at least two co-founders is ideal, and not just from an investment perspective. Our best investments often have at least one business founder (CEO) and one technical founder (CTO) to start, although we’ve seen successful examples that break this model.

We also want to see that the entrepreneurs are working on their businesses full-time, which shows “skin in the game,” and that they have a strong motivation to solve a specific problem. A founder with a fallback won’t chase profitability with the same hunger as an entrepreneur who cannot afford to fail.

2. Do the founders know their business, competitors, and industry?

We get hundreds of applications from startups in a wide range of industries, including pet commerce, last-mile delivery, and logistics. While these businesses might be good ideas or necessary for the region, they already have clear winners. For example, if we receive an application from a startup that wants to compete with Colombia’s Rappi in the on-demand delivery space without mentioning this massive competitor, it’s a red flag.

Invest in competitive research with Crunchbase Pro — try it free today.

Having competition or navigating a complex industry is part of founding a tech startup. However, as investors, we would prefer to hear founders directly address these challenges. Rather than hiding the harsh facts, we rather ask for help in facing them. If an entrepreneur can explain their business in one or two sentences and their most significant threat to building it, then they are on the right track.

3. Is the valuation in line with the industry and the region?

We are valuation-sensitive investors because there haven’t been many high dollar exits in Latin America. Valuations can vary by industry, and more importantly, by region. Therefore, it’s important that a startup’s valuation is in line with similar companies in the same industry, city, or region.

While exits and multiples are improving across Latin America, especially in Brazil, 2018 saw only a few $100M-$1B exits. The venture capital model doesn’t work based on shaky returns. A high seed or A valuation can make it very hard for startups to raise future rounds, or require them to do so at a down round. Asymmetrical valuation expectations can and do kill deals.

4. Why are they solving this problem?

The “Why” is often what motivates an investor to invest in a startup. There are two main reasons for this fact:

- Humans are naturally drawn to a great story. For example, people feel more motivated to back someone who is curing cancer to help their ailing sister than a wealthy founder looking to make a quick buck off the next Uber for Pets.

- The “Why” is what keeps founders motivated when the going gets tough.

Every startup reaches a moment when they need to pivot or change the model to solve the problem more efficiently. If the founders are more wedded to the “How” than the “Why,” then any pivot could kill the company.

5. Is the money machine working?

Once the team figures out how the company makes money, a strategic investment can be just what they need to take off. The money machine is working when a startup has figured out how one dollar invested can turn into two dollars profit, or better.

I’m always impressed by entrepreneurs who have bootstrapped their businesses for years and prioritize profitability. A great example of this phenomenon is recent YC-grad from Colombia, UBits, which was bootstrapped (and profitable) for four years before raising capital. In the absence of a robust VC ecosystem, founders have to get the money machine working fast, or risk failing.

6. Is the company a fit for the VC fund?

Many investors laugh at the fact that investment theses are made to be broken. As an investor, I’ve ignored our thesis more than once in the heat of the moment. Only later did I go on to regret it. While our firm will invest outside of our thesis in the case of a really killer company, the guidelines exist for a reason. If a startup applies from outside our focus area, they should explain why our firm is the right fit to help them grow.

Investors do not just create theses to have an excuse to reject startups. On the one hand, we base the thesis on which business models we think will be the most profitable or successful in the region where we invest. On the other, it also defines the industries where we believe we can be most helpful to entrepreneurs.

7. Does the startup have an “unfair advantage”?

A fantastic idea, a solid business model, and a rockstar team are all table stakes for receiving investment. However, what can make an investor take the leap is that secret sauce. It’s the magic ingredient that will allow the company to “win” and dominate the market.

Is the company already serving the largest client in the business? Does an industry titan back them? Did the founders sell a startup or build something huge in the past that failed? A VC will want to know about it. In a sea of applications, these factors make a startup stand out as a potential star. These are the startups to invest in and that could provide portfolio-defining returns.

Startup investment decisions are not as subjective as they seem. Every VC will have specific factors that motivate them to invest in startups. Most of all, I believe that startups should be so good that they (investors) can’t ignore you.

By Nathan Lustig, entrepreneur and Managing Partner at Magma Partners, a seed stage investment fund with offices in Latin America, the US, and China. Follow him @nathanlustig