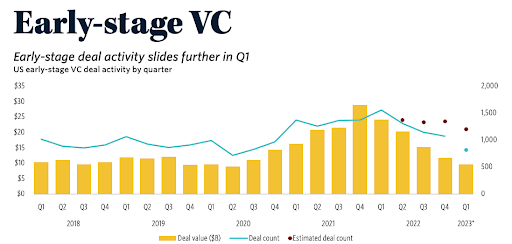

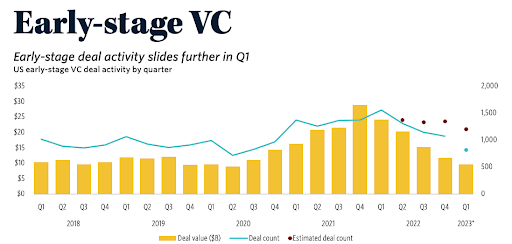

The stock market faced significant challenges in 2022, with the S&P 500 dropping by nearly 20% and the tech-heavy Nasdaq falling more than 33%. This market volatility drove valuations down and led to a 65% reduction in both IPO and M&A activity, resulting in a liquidity crunch for private-market investors. Consequently, the venture deal count for private companies declined 29% year over year, and early-stage venture deal activity in Q1 of 2023 witnessed a six-quarter consecutive drop in deal value, despite the common assumption that early-stage companies are insulated from market turbulence.

Early-stage deal activity, Pitchbook-NVCA Q1 2023 Venture Monitor, p. 12

In an economic downturn, startups face intense competition for limited funding, making it challenging to secure the necessary capital to sustain their operations. In this article, I’ll outline key trends in financing that startups should be aware of in order to stay competitive and move the fundraising process forward.

Making smaller rounds last longer

To adjust to the current market conditions, startups should consider lowering their fundraising targets, allowing longer durations between rounds and potentially accepting a lower valuation. Founders need to communicate these changes effectively to investors during the fundraising process. That includes updating the “Ask” section of their pitch decks to accurately reflect their company’s financial needs and the current market climate.

Lower valuations

Average Valuation, AngelList The State of U.S. Early-Stage Venture: 1Q23 report

There has been a notable decline in startup valuations across various funding stages. While pre-seed valuations increased slightly in Q1 2023, seed-stage valuations declined by 5.7%, Series A valuations dropped by 14.1%, and Series B valuations declined by 2.5% relative to the previous quarter.

For early-stage companies, these declines may not have a significant impact. However, for startups that have already raised capital and are looking to secure additional funding at higher valuations, the declining trend can pose challenges. This trend could be the primary reason why we see nonmarket standard deals from VCs, as founders may try to avoid raising funds at a lower valuation and, in turn, accept less-favorable deal terms they may not fully comprehend.

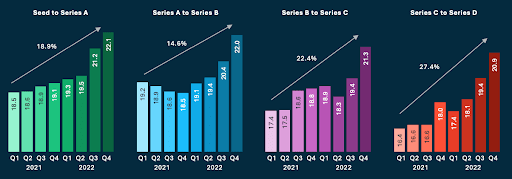

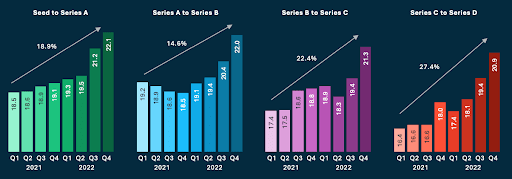

Longer time to fundraise

There has been an uptick in the duration between funding rounds for venture capital firms. As a result, startups are required to maintain their financial reserves for extended periods. Most investors are now urging their portfolio companies to secure sufficient funding to survive 18-24 months vs. 12-18 months historically.

Average Months Elapsed Between Rounds, SVB State of the Markets H1 2023

Raising less capital

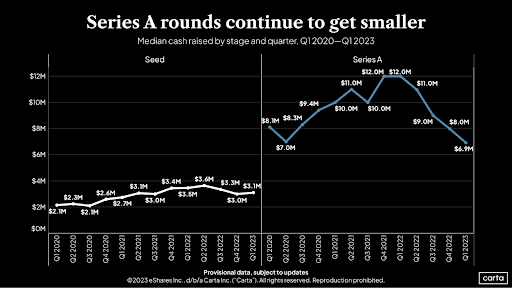

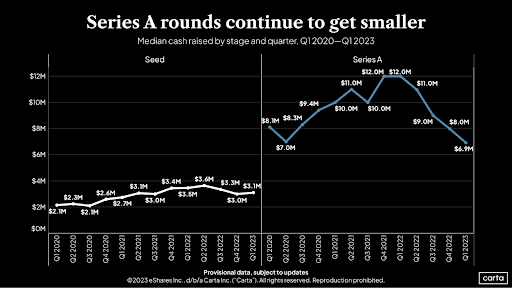

However, while it’s now more critical than ever to ensure the amount raised is sufficient to support operations for an extended period without the need for additional fundraising, startups are raising less capital per round on average. The median amount of cash raised across rounds is shrinking, which means capital efficiency and lowering burn rates are paramount.

Median Cash Raised by Stage and Quarter, Carta State of Private Markets: Q1 2023

Early-stage startups (SAFE financings)

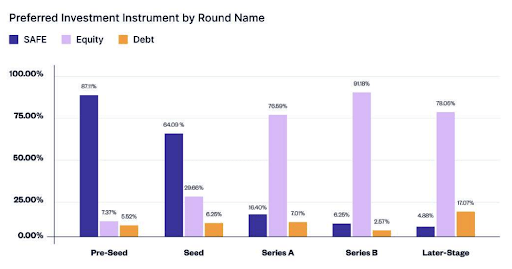

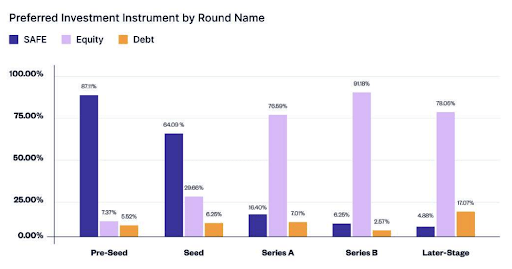

Moving on to deal mechanics, the vast majority of early-stage financings are typically conducted using SAFE (simple agreement for future equity) instruments — in fact, approximately 87% of pre-seed startups raised capital through a SAFE financing. Developed by Y Combinator in 2013, SAFEs are an appealing option for smaller rounds as they offer several advantages, which generally include:

- No need to determine the company’s value or price per share;

- No negotiation on governance or control (other than potentially providing investors with a side letter for board observer or pro rata rights);

- No board seats for investors;

- No information rights to investors;

- No voting rights for investors;

- No interest rate; and

- No maturity date.

SAFEs essentially grant investors the right to convert their investment into equity at the next qualified financing round. This conversion feature provides investors with the potential for future returns, while allowing founders to secure funding without the need to set a valuation or establish governance terms.

My suggestion for startups at the pre-seed or seed stage is to leverage the market standard SAFE financing documents found on Y Combinator’s website. By using these market standard documents, founders can streamline the fundraising process and avoid complex negotiations with investors who may require legal counsel to review nonstandard venture contracts.

Preferred Investment Instrument by Round, AngelList The State of U.S. Early-Stage Venture: 1Q22 report, p. 9

Y Combinator primarily maintains two types of SAFEs — a post-money valuation cap only SAFE and a post-money discount only SAFE (and an MFN SAFE not covered here).

Valuation cap only SAFEs set a ceiling on the company’s valuation when the SAFE converts into shares. This means that the investor is guaranteed to convert their SAFE at a price that is not higher than the specified valuation cap, regardless of the company’s value at the next funding round.

In contrast, a discount only SAFE provides the investor with a discount on the price per share that they will convert at, as compared to future equity investors. For example, if the discount is set at 20% (15%-25% is standard), the investor will purchase shares at a price 20% lower than the price per share paid by the next equity investor.

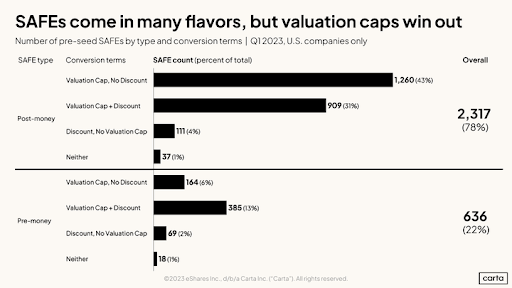

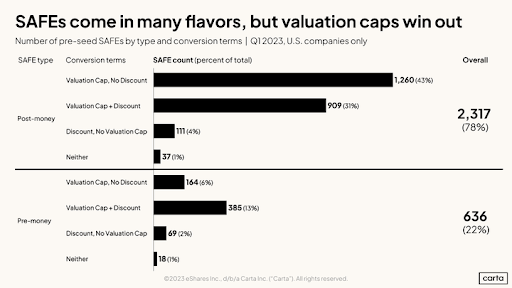

Post-money valuation cap only SAFEs are the most popular choice for founders and investors today, accounting for 43% of all SAFEs issued. By using market standard documents, founders can streamline the fundraising process.

SAFEs come in many flavors, Carta Data Minute

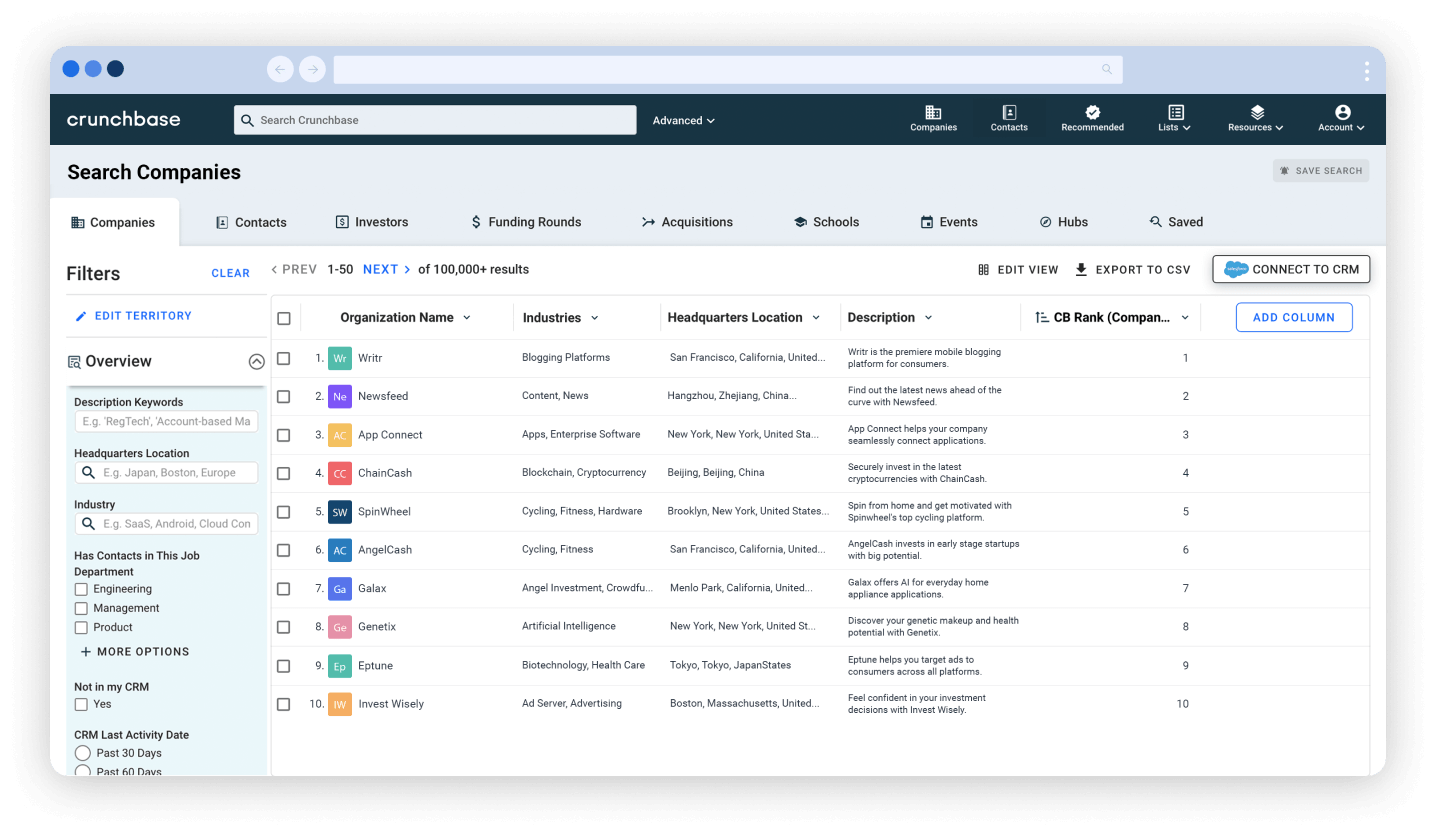

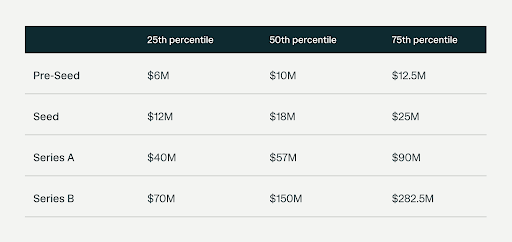

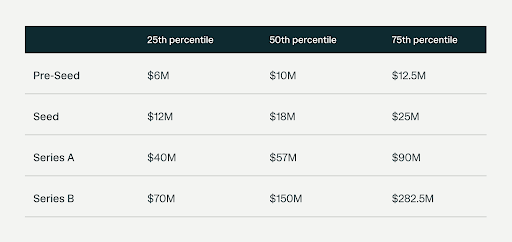

Determining the appropriate valuation cap for a SAFE can be challenging, but AngelList’s valuation benchmarks are reliable and accurate.

Median Valuation, AngelList The State of U.S. Early-Stage Venture: 1Q23, p. 7

This is further validated by what I’m seeing from early-stage investors. While the typical range for post-money valuation caps varies depending on the stage of the company, it’s common for post-product, pre-revenue startups to have a post-money valuation cap of around $8 million-$10 million.

Software valuations by milestone, LinkedIn, Ihar Mahaniok

Seed and above (preferred stock financing)

Preferred stock financings are a common arrangement between venture capitalists and startups, allowing investors to purchase shares of preferred stock with various rights and preferences. These agreements are designed to mitigate the risks of investing in early-stage startups raising significant capital.

The National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) model term sheet is the market-standard template that most venture capital term sheets are based on, and it includes around 40 negotiable provisions. In times of tightened capital availability, founders should be aware of common deviations from market-standard provisions. It’s also important to note that term sheets set a precedent for future financings; investors will have access to historical deal documents, and if they see preferential treatment that was offered to investors in a previous round, it may be difficult to negotiate those rights away for future investors.

In the following sections, I outline three control provisions — frequently negotiated in economic downturns — commonly overlooked by founders.

Liquidation preference

Liquidation preference is an investor’s right to receive their investment back before common stockholders, which include a company’s founders and employees. In a liquidation event such as the sale of the company, the liquidation preference dictates the amount of money that must be returned to investors before the company’s founders or employees receive returns.

1x nonparticipating preferred has been the standard for a long time and is used for downside protection. This is where investors have the option to either receive an amount equal to the liquidation preference multiple, in addition to any unpaid dividends, or convert their preferred shares into common stock and participate in the liquidity event as common shareholders.

For example, if an investor has a 20% ownership stake in a startup and invested $2 million with a 1x nonparticipating liquidation preference, and the company is sold for $3 million, the investor has the option to either exercise the 1x liquidation preference and receive $2 million back, or be treated as a common shareholder and receive 20% of $3 million.

On the other hand, with a fully participating liquidation preference, investors “double-dip” in the liquidation proceeds, meaning they receive their investment back first, and then also participate in the remaining proceeds in proportion to their ownership stake in the company.

For example, if an investor has a 20% ownership stake in a startup and invested $1 million with a fully participating liquidation preference, and the company is sold for $9 million, the investor receives $1 million (their investment) and $1.6 million (20% of the remaining $8 million). For sake of comparison, if the liquidation preference here was 1x nonparticipating, the investor would forgo their $1 million liquidation preference, and instead choose their 20%, which would result in $1.8 million. So, because of the participation feature, the investor is receiving an additional $800,000 as compared to the nonparticipating liquidation preference.

I’ve recently noticed an uptick in nonparticipating preferred liquidation preference with higher multiples (for example, 2x nonparticipating preferred) as well as a higher frequency of deals with 1x participating preferred.

Protective provisions

The protective provisions typically included in a term sheet are designed to protect the preferred shareholders’ minority stake from the actions that could be detrimental or have a material effect on the preferred shareholders’ investment. These provisions often include the right to approve any sale or liquidation of the company, the right to approve any changes to the company’s charter or bylaws, the right to approve any new securities issuance that could dilute the preferred shares, the right to approve any debt financing that could significantly impact the company’s financial position, and the right to approve any dividends or stock buybacks.

By negotiating for protective provisions, the preferred shareholders can ensure that their investment is safeguarded and that they have a voice in important decisions that could impact the company’s future success.

Price-based anti-dilution

Price based anti-dilution provisions are designed to protect investors in case the company issues new shares at a price lower than the price investors paid in the previous round. There are two common types of anti-dilution provisions: full ratchet and broad-based weighted average.

Full ratchet is the more severe of the two provisions. In the event of a down round, the previous financing price is reduced to the price of the new issuance, effectively erasing the original investor’s equity premium. This provision is less common because it can be harsh for the company’s founders and employees, who may lose a significant amount of their equity.

Broad-based weighted average is the more common provision — it takes into account the total number of shares issued in the down round and how it impacts the overall valuation of the company. The formula used to calculate the new price for the previous financing is based on the weighted average of the old and new prices.

For example, if a startup raised a $10 million Series A at $1/share and in the future raised a $500,000 Series B at 50 cents/share, the full ratchet provision would reprice the Series A at 50 cents/share, while the broad-based weighted average would consider the total number of shares issued in the down round and the resulting impact on the overall valuation of the company.

Founders should be aware of the anti-dilution provisions included in their term sheets, as they can have a significant impact on the equity ownership of the company.

Closing notes

It’s crucial for founders to work with a competent and experienced venture attorney who can provide valuable guidance and support throughout the fundraising process. In many cases you will be the least experienced person around the negotiating table. VCs negotiate tens of deals a year and most founders will fundraise once every 18 months or so. A great lawyer has access to deal mechanics from hundreds of transactions a year and thus is worth the investment. A skilled lawyer can help founders navigate the negotiation process, identify potential risks and pitfalls, and ensure that the deal terms align with the company’s long-term goals and objectives.

Sarosh Shahbuddin is the CEO and co-founder of Dori, a cutting-edge generative AI platform that simplifies and streamlines venture equity transactions. Prior to founding Dori, Shahbuddin served as the head of product and engineering at Pindrop, a voice security startup backed by major players like Andreessen Horowitz and Google Ventures. There, he focused on developing natural language processing and machine-learning technologies for voice-enabled devices, helping to establish Pindrop as a leader in its field. He holds a degree in electrical engineering from Georgia Tech and has been an active member of the Atlanta tech community for several years.